How do you extract the rennet from the thistle? A Google search for "Thistle Rennet" turns up pages that reference the book "The Encyclopedia of Country Living:

An Old Fashioned Recipe Book" by Carla Emery. This book recommends the following:

Gather the thistle flowers when they have turned brown. If you see thistledown, the plant is over-mature. Get it right after the end of bloom and before the stage where down blows away. Air dry the flowers.

This confused me because everything I had read and heard on the subject indicated that the purple stamens were the part of the plant that held the rennet. Not wanting to waste my thistle or my expensive raw milk, I sent an email to cheesemaker Alyce Birchenough of Sweet Home Farm. Alyce was mentioned in a spring 2010 Culture Magazine article on thistle based rennet cheeses and she was kind enough to reply to my query with information she received when watching the cheesemaking procedure in Italy:

Cardoon (Cynara cardunculus) is commonly used in Spain and Portugal as a vegetal rennet to coagulate sheep milk cheese. The following notes were obtained at Corfilac in Ragusa, Sicily at Cheese Art 2006 at a hands on demonstration workshop.

The part of the cardoon used to coagulate milk for cheesemaking is the lavender stamens that appear when the plant is in bloom. The stamens may be plucked or cut away from the base with a knife. The stamens should be dried at room temperature for about 3 weeks with periodic stirring to prevent mold growth. The dried stamens will keep for 2 years.

In a mortar and pestle or a blender grind the cardoon stamens to a powder. Suggested use rate is 1 gram of dried flower per liter of milk. The ground stamen should be steeped in room temperature water at the rate of 1 gram stamen to 10 ml water. Steep the mixture for 30 minutes. Strain through a paper filter before use. Add to the ripened milk at 30 C or 86F. i.e. 100 ml solution for 10 liters of milk. Coagulation should occur in 30- 45 minutes. Fresh flowers may also be used and the usage may be slightly reduced since the activity is stronger when fresh. This coagulant is more proteolytic and will produce a softer cheese.Proceed with the make procedure as desired.

This information made a lot more sense to me, and it had precise measurements to follow. I was very excited and I decided to modify a Camembert recipe to use this rennet.

Thistle based rennet produces a bitter flavor if used with cow milk if the cheese is not eaten within a few days. This is because unlike traditional rennet enzymes, which only trim off the ends of the milk casin proteins, thistle rennet cleaves the casin proteins at many points. In cow milk this results in a bitter flavor, but not in goat or sheep milk. Therefore I was destined to make my first goat milk cheese.

I obtained two gallons of goat milk from a local goat farm called Terra Farma, and I used 1.5 gallons to make cardoon cheese. The remaining half gallon became fresh chevre, a recipe I in which had some confidence and therefore guaranteed me at least one good cheese from my first experiment with goat milk. The milk had a slight hint of the "barnyardy" flavor, which I associate with goat milk, but otherwise seemed very fresh.

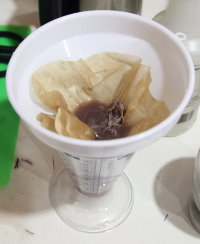

I ground up the stamens with a pestle and mortar, and mixed with 70 ml of boiled and cooled water. I allowed the mixture to steep for 30 minutes while my milk was culturing, then I filtered it through a coffee filter and used it as just as regular rennet.

I must mention that lack of sanitation of this process had me a little concerned. The thistles came in fresh from the garden where the local honey bees had just been busily rooting around in them searching for nectar. I was concerned about deactivating the enzyme and so I used no sanitizers on the thistles other than a rinse in tap water before cutting. A little bit of the local bacterial fauna is bound to get in one’s homemade cheese, and might impart a local flavor unique to the cheesemaker. If any of my cheeses were going to have a local flavor, this would be one.

I modified a Camembert recipe for use with this cheese, as I wanted something that would age quickly. I did not add mold spores to the cheese, as I would for Camembert, as I wanted any flavors derived from the rennet to not be overpowered. I understand that the proteolysis, or protein splitting properties of thistle rennet tends to create a runny cheese. This reminded me of the runny center of Camembert, which is why I choose it as my starting point.

To 1.5 gallons of goat milk warmed to 86F I added 4 ounces of frozen mesophilic culture and I allowed this to culture for 45 minutes. Then I added the 70 ml of rennet prepared as described above. 45 minutes later, I checked the milk to find it nicely coagulated. I was very pleased with myself. Until this point I strongly suspected that this was not going to work, and I was very excited this was not the case.

I cut the curd to 1 inch cubes, allowed them to heal for 10 minutes, then stirred gently for 20 more minutes, all while keeping the milk at 86F. After stirring I let the curds settle and mat, and then transferred to round molds on top of draining mats. As I would for Camembert, I did not press the cheese, but rather flipped the molds at regular intervals, allowing the curds to mat under their own weight.After 24 hours of draining, I removed the molds. They cheeses started to barrel immediately. The sides bowed outward and the cheese could not hold its own shape now that the walls of the mold were no longer keeping it confined. I feared that I had not extracted enough whey from the curds during cooking. When I repeat this experiment, I will probably cut to smaller 1/2 inch cubes, or even smaller. To keep the cheeses from barreling too much I wrapped them with a strip of cheesecloth similar to the wrapping I had seen on traditional thistle cheeses in the spring issue of Culture Magazine. Apparently this is a traditional wrapping to keep the cheese whole as the proteolytic enzymes in the thistle rennet turn the center of the cheese very runny.

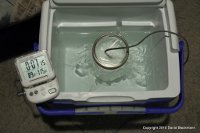

Since the cheeses seemed too moist I decided to let them dry for two days at room temperature. Then I moved them to my wine refrigerator turned aging cave. Normally I keep cheese in some sort of container in this wine refrigerator because its circulation fans tent to dry out the cheese. This time I waited a week before transferring them to containers, again because I felt the cheeses were too moist.

As I write this, the cheeses have been aging two weeks. One has dried out quite a bit more than I would like while the other one seems perfect except for a little bit of blue mold, which I wiped off with a mixture of vinegar and salt. I hope to age these for at least 6 weeks before trying them, but I will have to keep a closer eye on them from now on. Stay tuned for future updates.