Base Recipe: Pecorino Fresco Bianco

(This is the base recipe for most of Podere Paugnano's other cheeses and I'll refer to it in all other pecorino entries.)

One of the simplest and the freshest cheese made at Podere Paugnano was their Pecorino Fresco Bianco, which translates to Fresh White Sheep-Milk Cheese. It is fresh and white because it hasn't had a chance to develop any rind. They used the same recipe for the Fresco Bianco as for their aged cheeses, but stored it at a cooler temperature and sold it within 10 days of production.

All sheep milk cheeses are called pecorino. In Italian pecora means sheep, and pecorino is the name for any sheep milk cheese. You'll see in this recipe and the recipes that follow that pecorino cheeses in Italy come in a much, much wider variety than pecorino in the US, where pecorino usually refers to a variety aged 12 months or more so that it is hard enough for grating. At least 95% of what the Porcus produced was aged less than a year.

One thing you'll notice right away about the recipe is that it does not call for any starter culture. Podere Paugnano produced all organic, raw cheeses and did not use any cultures, which is the traditional method of pecorino production. Even the other creamery I visited was surprised at this technique. It is surprising because it is somewhat risky from a health and consistency perspective: starter cultures tend to crowd out any less-desired or harmful bacteria in the milk and also impart a fairly consistent flavor. And yet this technique allows the terrior to shine through.

Ingredients:

12 liters raw sheep milk

7 g rennet dissolved in water just before adding to milk

Notes:

- They used animal rennet in paste form or vegetable rennet in liquid form, depending on the batch

- The rennets used in Italy are 1:20,000 (single strength) and 1:10,0000 (double strength) while the rennet we use in the US is typically 1:15,000 (single strength) and 1:7,500 (double strength). So for this recipe, 7g of single strength Italian rennet is equal to 9 1/3g of single strength American rennet.

Instructions:

1. Heat milk to 40C.

2. Add rennet and stir for 1 minute.

3. Let set for 20 minutes, or until clean break (I was visiting at the end of the lactation cycle and due to the impact of the sheep's hormonal changes on the coagulation properties of the milk it took about an hour for the milk to set. So the set time can vary tremendously based on season.)

4. Cut curd into corn size pieces, then continue to agitate for 15 minutes, maintaining the curd at 38-40C the entire time.

5. Pour into molds (no leader needed). (They typically used approximately 8-inch high, 8-inch diameter molds)

6. Use hands to press curd in molds and expel whey. As curds compress, add more curd and repress so that curd is level or nearly level with top of mold.

7. Maintain temperature of curd at 38-40C while allowing to drain freely for 45 minutes. The Porcus used a covered draining table that they filled with steam.

8. Flip cheese in the mold. (No need to apply pressure again.)

9. Return to 38-40C environment for 45 minutes.

10. Flip again.

11. Return to 38-40C environment for 20 minutes.

12. Keep cheese in molds and transfer to room temperature rack. Store at room temperature for 1 day.

13. After the day at room temperature, unmold, flip, apply a thin coating of salt to the surface of the cheese and return to mold. Let sit for 5 hours per kilogram of cheese. (For example, if you have a 1 kg cheese, let salt sit on cheese for 5 hours. If you have a 2 kg cheese, let salt sit on cheese for 10 hours.)

14. After the salt has absorbed for the appropriate amount of time, unmold and rinse salt from cheese.

15. Place unmolded cheese in 8C environment for up to 10 days.

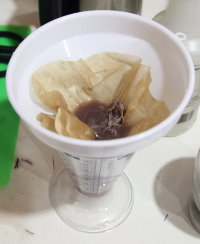

Tool used for curd cutting as well as agitating the curd after cutting

Pressing the curd and then adding more curd to each mold as the curd level dropped due to whey expulsion.

Final hand pressing of the curd.

Flipping the cheese

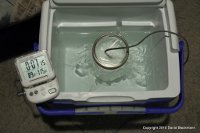

The "fresh cheese" aging room, kept at 8C

Pecorino Fresco Abbucciato

This is a fresh sheep milk cheese "with skin" (abbucciato). It is made using the exact same recipe as Pecorino Fresco Bianco, but oiled (to aid in rind development) and aged longer.

Instructions:

Follow steps 1-14 in the Base Recipe: Pecorino Fresco Bianco.

15. After 10 days of aging at 8C, apply a thin coating of olive oil to the cheese. This is an optional step. Alternately, Giovanna mentioned that she sometimes likes to coat with tomato juice instead of olive oil.

16. Return to 8C storage for up to 3 months.

17. Wash mold from cheese with water and pat dry before cutting/serving.

Oiling the cheese after 10 days aging. These wheels will then return to the aging room for further aging. (Two unidentified types of pecorino are being oiled in this photo.)"

Pecorino Fresco Abbucciato ready for sale

Pecorino Erborinato

This recipe is for a sheep milk blue cheese, but I have no idea what makes it blue. I watched Giovanni make a batch of this and he didn't add any molds or culture and they don't poke any holes in it. When it does get some blue, it's only a small amount (as far as I could see in the wheels they broke open while I was there). I found that I particularly enjoyed the flavor of this cheese because it was not too sheepy and had a creamy flavor.

The instructions are identical to the Base Recipe: Pecorino Fresco Bianco, but with slight changes in all of the target temperatures and a longer aging period. Even though this is aged for up to 4 months, the Porcus still considered this a fresh cheese. I think this was mainly because it was aged in the 8C cave with the other fresh cheese.

Instructions:

1. Heat milk to 38C.

2. Add rennet and stir for 1 minute.

3. Let set for 20 minutes, or until clean break.

4. Cut curd into corn size pieces, then continue to agitate for 15 minutes, maintaining the curd at 43C the entire time.

5. Pour into molds (no leader needed). (They typically used approximately 8-inch high, 8-inch diameter molds)

6. Use hands to press curd in molds and expel whey. As curds compress, add more curd and repress so that curd is level or nearly level with top of mold.

7. Maintain temperature of curd at 30C while allowing to drain freely for 45 minutes. The Porcus used a covered draining table that they filled with steam.

8. Flip cheese in the mold. (No need to apply pressure again.)

9. Return to 30C environment for 45 minutes.

10. Flip again.

11. Return to 30C environment for 20 minutes.

12. Keep cheese in molds and transfer to room temperature rack. Store at room temperature for 1 day.

13. After the day at room temperature, unmold, flip, apply a medium coating of salt to the surface of the cheese and return to mold. Let sit for 5 hours per kilogram of cheese. (For example, if you have a 1 kg cheese, let salt sit on cheese for 5 hours. If you have a 2 kg cheese, let salt sit on cheese for 10 hours.)

14. After the salt has absorbed for the appropriate amount of time, unmold and rinse salt from cheese.

15. Place unmolded cheese in 8C environment for 10 days.

16. After 10 days at 8C, apply a thin coating of oil.

17. Return to the 8C environment for 1 to 4 months.

18. Wash mold from cheese with water and pat dry before cutting/serving.

The salting step for a batch of erborinato